World Malaria Day reminds us, as if we had ever forgotten, that fatal diseases that have afflicted humanity long before COVID-19 are still responsible for hundreds of thousands of avoidable deaths each year.

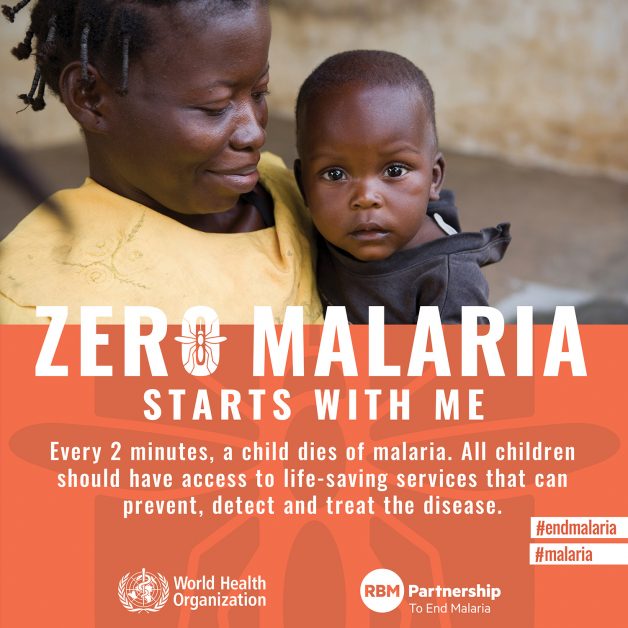

It is a time to reflect that, in a world where heart-breaking images of children suffering from famine, war and neglect can spur us into action, the devastating impact of malaria on the youngest infants in sub-Saharan Africa can easily be overlooked – crowded out by more immediately dramatic events.

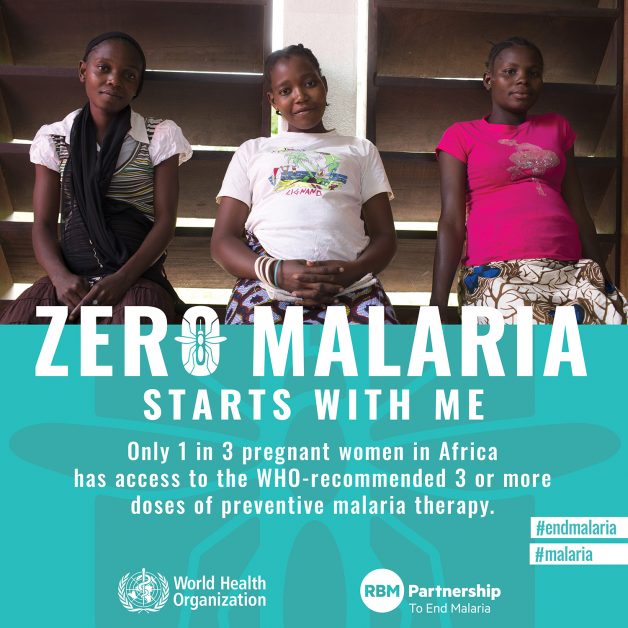

The WHO’s World Malaria Report revealed that in 2019 there were 409,000 deaths from malaria, the vast majority of them children under 5 years. As the COVID-19 pandemic diverts resources away from malaria control efforts, there is fear that much of the progress made in recent years could be undone. As Prof. Ric Price of the Menzies School of Health stated recently, “Unless malaria elimination remains high on our priorities during the COVID-19 pandemic, the dire consequences of resurgence will be felt for years to come”.

Malaria still affects some 3 billion people in 95 countries. But deaths, thanks to the use of interventions such as insecticide-treated bed nets and the use of artemisinin-based combination therapies, fell some 60% between 2000 and 2015, with big improvements in Africa where 93% of cases are found. Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa, highlights what this has meant to people living there: “In the past twenty years, more than 1.2bn malaria cases, and 7.1m deaths, have been averted in the region.” Despite these remarkable achievements, recently progress has stalled.

Clearly, resting on our laurels is not an option as the coronavirus pandemic has proven on a daily basis, constantly catching us out. But there are ways forward. As Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director General, has said: “We need a more efficient, effective and equitable response to end malaria”.

Fighting the fakes

One effective and equitable response from the world would be to stop the spread of counterfeit and sub-standard medicines and treatments, especially in Africa, which has reported the highest incidence of falsified and substandard medicines. It has been reported that as many as 60% of antimalarials circulating in sub-Saharan Africa could be poor-quality, substandard and falsified, and an estimated 122,350 under-five malaria deaths in the region were associated with consumption of poor-quality antimalarials in 2015.

Prof Paul Newton of the Centre for Clinical Vaccinology and Tropical Medicine at Oxford University, has spoken recently of “a parallel pandemic, of substandard and falsified products.” Bottlenecks and breakdowns in supply chains, overstretched public health services, travel bans and, ironically, poverty in desperate people are just some of the factors behind this.

One effect is, inevitably, to inflate prices. According to the BBC, chloroquine, normally sold for about $40 a pot of 1000 tablets, is fetching up to $250 for pharmacists in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Prof Newton and colleagues suggest that one has to distinguish between fake drugs that contain no active ingredient and sub-standard or counterfeit ones that do, including the wrong ones or those that are contaminated. “They are an inevitable consequence of inadequate local regulation of the pharmaceutical industry and the lack of good manufacturing practices (GMP) facilities in many ‘developing’ countries.”

Accelerating resistance to medicines

To compound these worrying trends there is mounting evidence that falsified and sub-standard medicines are driving up antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to drugs, including antibiotics. This in turn can help the emergence and spread of drug-resistant pathogens.

“Substandard or falsified medicines not only have a tragic impact on individual patients and their families, but also are a threat to antimicrobial effectiveness, adding to the worrying trend of medicines losing their power to treat,” according to Dr Mariângela Simão, Assistant Director-General for Access to Medicines, Vaccines and Pharmaceuticals at WHO.

Resistance to artemisinin has been spreading across the Greater Mekong sub-Region of South-East Asia. Markers of resistance have already been detected in Africa, although existing medicines still remain effective. If resistance – encouraged by falsified or sub-standard medicines containing less than the efficacious dose of active ingredient – were to take hold in Africa, the result could be a public health disaster of unprecedented gravity.

Stepping up to the challenge

Several factors are crucial in the fight against malaria: improvements in vector control (mosquito nets/repellents); better and more widespread use of diagnostics, effective medicines and robust efficacy surveillance. In the last decade 3.1bn courses of artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs) were used. ACTs are the gold standard. They have a massive impact with greater than 95% efficacy and it would be a tragedy if we lost them.

It is vital that we keep ACTs alive for as long as we can. Meanwhile, a number of strategies to mitigate the emergence of resistance are being explored. These include the deployment of multiple first line therapies simultaneously – which modelling has suggested may significantly slow the development of resistance, the use of triple ACT combinations and the development of new non-artemisinin compounds. All these efforts could, however, be undermined by the presence of falsified and sub-standard anti-malarials.

Key to rebooting global efforts to eliminate malaria, even during the pandemic, is to pull out all the stops in ensuring that countries do not scale back prevention, diagnostic and case management activities.

Equitable, global solutions are critical. Just as the world needs to redouble its efforts to ensure that the much-vaunted COVAX facility delivers its promise of vaccine deliveries to the poorest nations so we have to break the fakes damaging the fight against malaria by planning for shared production, equitable distribution and enhanced quality monitoring.

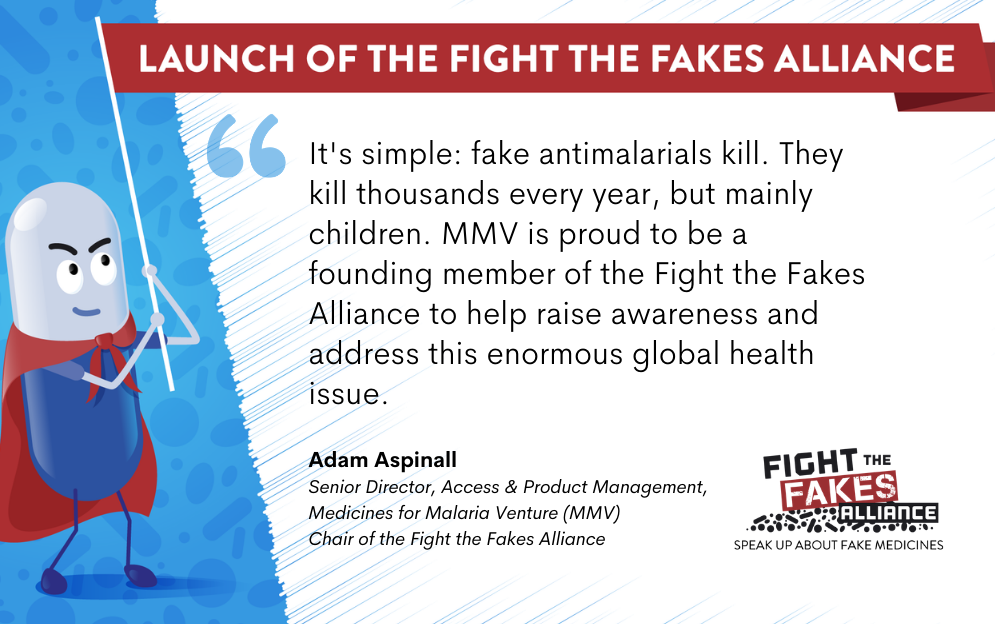

Dr Tedros is right to underline this message: “‘Nobody should die from malaria, a disease that is preventable and treatable.” We at MMV are more than ever determined to be part of the solution. As a founding member of Fight the Fakes Alliance, we are taking the issue to the next level through important raising awareness efforts and hopefully more action on the ground in the close future. It is vital to inform the public about falsified antimalarials, their prevalence and associated risks but also to educate them so they can better protect themselves.