Homicide Charges for Those Making Harmful Fake Medicine?

Article originally published on Health Policy Watch by Kerry Cullinan

There should be much harsher penalties, including homicide charges, for those who intentionally falsify medicine and include harmful ingredients, according to Kawaldip Sehmi, CEO of the International Alliance of Patients’ Organisations (IAPO).

Sehmi was speaking at an event hosted by Fight the Fakes Alliance in Geneva on Wednesday to highlight the global proliferation of fake medicine and the threat it poses to patients.

In October, 99 children died in Indonesia from cough syrup contaminated with anti-freeze chemicals.

The previous month, 66 children died in The Gambia – also from contaminated cough syrup. These tragedies echo the deaths of 12 Indian children in 2020 – from cough syrup that had been rendered poisonous after one of the ingredients was replaced by a toxic one.

Yet, said Sehmi, most countries treated falsified medicines as a commercial crime such as “product liability or negligence” when they should be treating it “in the same way as narcotics”.

“Trust is at the heart of everything. Patients have to trust that the product they’re getting is of the appropriate quality and safety,” said Pernette Esteve, who heads the World Health Organization’s (WHO) team on substandard and falsified medical products.

“Gaining the confidence of the public once you’ve lost it is very difficult. Think back to the COVID pandemic. Making sure that people trusted the vaccines, vaccine acceptability, was a key point.”

For 10 years, the WHO has been building a database of substandard (unintentionally defective) and falsified (deliberately altered) medicine to understand the scope, scale and harm.

From this database, the WHO has identified the three driving forces: lack of access to medicine, poor governance including corruption, and weak technical capacity, said Esteve.

The WHO’s response was based on “prevention, detection and response”, she added.

The extent of the problem

Stanislav Barro, Novartis’s global head of anti-falsified medicines, says that his company has confronted fake medicine in every region of the world.

The timely authentication of medicines was both the biggest challenge and the biggest opportunity to stamp out fakes, he said – but warned that it is “a very complicated process”.

All the suspect samples have to be brought to a place where they can be actually properly authenticated using forensic means,” said Barro.

However, almost 50 pharmaceutical companies were now sharing data via the Pharmaceutical Security Institute, and there had been a 38% increase in the incidence of falsified medicines between 2016 and 2020 in 142 countries, and incidence had surged in 2021 during the early days of the COVID pandemic.

“Basically, this is whatever the criminal organisations can make money with. It doesn’t really matter whether it’s falsified, tampered, stolen, illegally diverted. It’s a bit of everything, quite frankly,” added Barro, noting that it usually meant “terrible news for patients”.

“We need to find solutions to leverage digital technologies to localise authentication, identify falsified medicines and make that timely. Cut down these timelines from weeks to basically days, hours if possible, and accelerate the reporting to local authorities and to the WHO.”

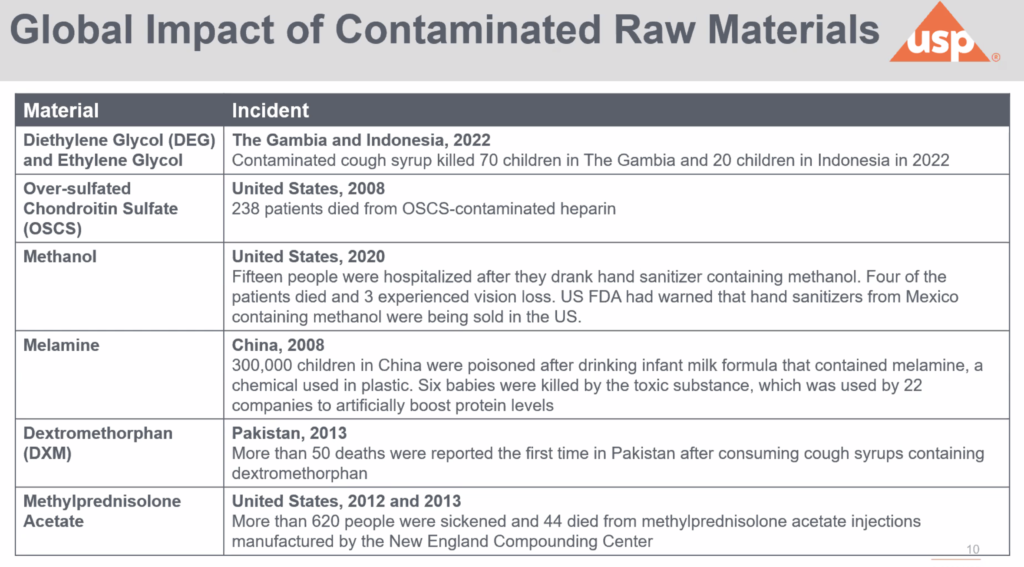

Policing raw materials

Sireesha Yadlapalli, vice president for international government and regulatory affairs for United States Pharmacopeia (USP), called for more policing of raw materials.

Medicines are made of two components, the active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) and the inactive ingredients or excipients, including reagents, solvents and items related to the taste or look of the product.

There was less stringent policing of the excipients, and these were often where problems arose, Yadlapalli said.

“There might be an issue with an ingredient but the manufacturer may not know about that particular issue because he just took the supplier’s word and certificate of analysis at face value, and that’s because raw materials are not being tested when they’re accepted from suppliers,” she added.

“Manufacturers need to test the raw materials. Regulations should be put in place requiring testing of these raw materials.”

Improving regulatory systems

Members of the International Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Association made up to 80% of quality-assured medicines around the world, according to its general secretary, Suzette Kox.

“We think that the biggest challenge is weak healthcare systems which includes, of course, the insufficiently resourced regulatory system and quality control. Most countries around the world do not have proper regulatory systems in place, and also no proper competition policies.”

Oksana Pyzik, who lectures at the UCL School Pharmacy, said that one of the biggest challenges is a lack of public awareness.

Pointing to the proliferation of online medical supply outlets during COVID-19, Pyzik said that many patients didn’t know how to verify legal online pharmacies.

“Pharmacists are the last line of defence before patients received those medications and take them home with them. And there’s a real opportunity there for patient education as part of wider public awareness,” she said, adding that this was why educating pharmacists about falsified medicines was essential.